Guest author: Paulo Anciaes, Senior Research Fellow – Transport Behaviour Modeller, Bartlett School Env, Energy & Resources, Faculty of the Built Environment, University College London.

Key messages

- Roads are barriers to pedestrians.

- These barriers are linked with less walking and poorer social capital, health and wellbeing.

- The wider impacts of the barriers can be estimated in terms of money.

- There are several possible interventions to reduce the effect but, until now, there were few tools to support the assessment of these interventions.

- This blog will show new tools, developed at UCL.

- Some of the tools can be used by the public, facilitating the public participation in decisions that affect pedestrians.

1. Cars are a problem for pedestrians

Roads can be unpleasant and dangerous for pedestrians, both when they have lots of traffic and when they have little traffic but vehicles move at fast speeds. This can force pedestrians to make detours to cross the road in a safe point with a crossing facility. When they arrive there, they may have to wait for the green signal or go up and down stairs to use a footbridge or underpass, which may be dark, flooded, or full of litter. People who face these problems on a daily basis start to perceive the road as a physical and psychological barrier.

At UCL (University College London), we have been studying this problem since 2014, collaborating across disciplines and countries. We have looked at several UK case studies where roads have been a barrier for pedestrians for decades. A notorious case is Finchley Road in North London: a 4-lane road cutting through a high street. In the only places where pedestrians can cross safely, they wait up to 2 minutes for the green signal to cross half of the road. If they do not walk fast enough, the signal becomes red and they then have to wait another 2 minutes in a pedestrian refuge to cross the other half of the road.

The problem is widespread. For example, in cities such as Bogotá, Sao Paulo, and Santiago the problem is not only getting worse but it also disproportionately affects poorer people. In developing countries, the problem is just emerging because of the upgrade of road infrastructure and increase in car use. For example, in Praia, the capital of Cabo Verde islands, in some neighbourhoods, busy roads disrupt more than 70% of potential trips to local shops (Anciaes and Nascimento 2022).

2. Why does it matter?

Busy roads are a problem because they discourage walking. In a national-level study, we found that people who live near ‘less crossable’ roads tend to walk less for transport and for leisure. This leads to an estimated loss of 1 billion local trips per year in Great Britain. Less walking is then associated with fewer social connections and poorer health and wellbeing (Anciaes et al. 2022).

Looking at some neighbourhoods in detail (including Finchley Road), we have also found that the worse the traffic-related walking problems, the higher the probability of having poor health (Higgsmith et al. 2022) and lower wellbeing (Anciaes et al. 2019).

While these impacts on social capital, health, and wellbeing are not economic, they can still be expressed in terms of money, using economic valuation. But the problem also has purely economic impacts. Less walking means less money spent on local shops: even though people driving to shops spend more per trip, they also make fewer trips. Over a year, people who walk spend more. We estimated that the value of all these non-economic and economic impacts in Great Britain is £631 per person on average, or 1.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (Anciaes et al. 2022).

3. What can be done?

The good news is that many governments are interested in reducing this problem, as this fits their sustainability and urban liveability agenda. Giving more priority to active modes of transport, such as walking and cycling, reduces noise, air pollution, and global emissions, while also providing more opportunities for people to enjoy the city. Examples of interventions that have been used in cities around the world include:

- More and better crossings

- Less hostile road designs, with fewer road lanes, wider middle strips, better street furniture, and greenery

- Less hostile road environments, with less traffic and reduced speed limits

- Shifting the road up (flyover), down (tunnel) or to another place (bypass)

4. What tools we can use to reduce the barrier effect of roads?

At UCL, we have developed several sets of tools to support decisions for the implementation of the solutions described above

4.1 Tools to identify barrier effects

Use them if: you are a practitioner at a government or company/NGO and have some resources to collect data

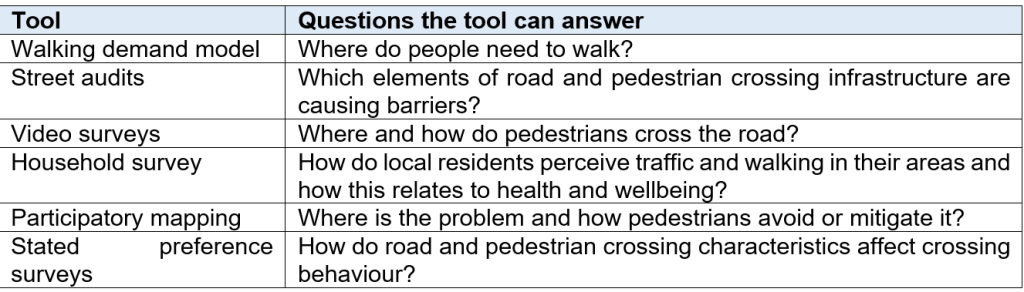

The Street Mobility Toolkit, available from the UCL website, contains guidance to use the following tools to identify barrier effects of roads on pedestrians.

4.2 Tools to generate solutions for barrier effects

Use them if: you are a practitioner or a member of the public and you want to know possible solutions to improve walking conditions in a busy road. You are aware that some solutions affect other road users (e.g., cars, buses, cycles) and you have thought about whom to give priority.

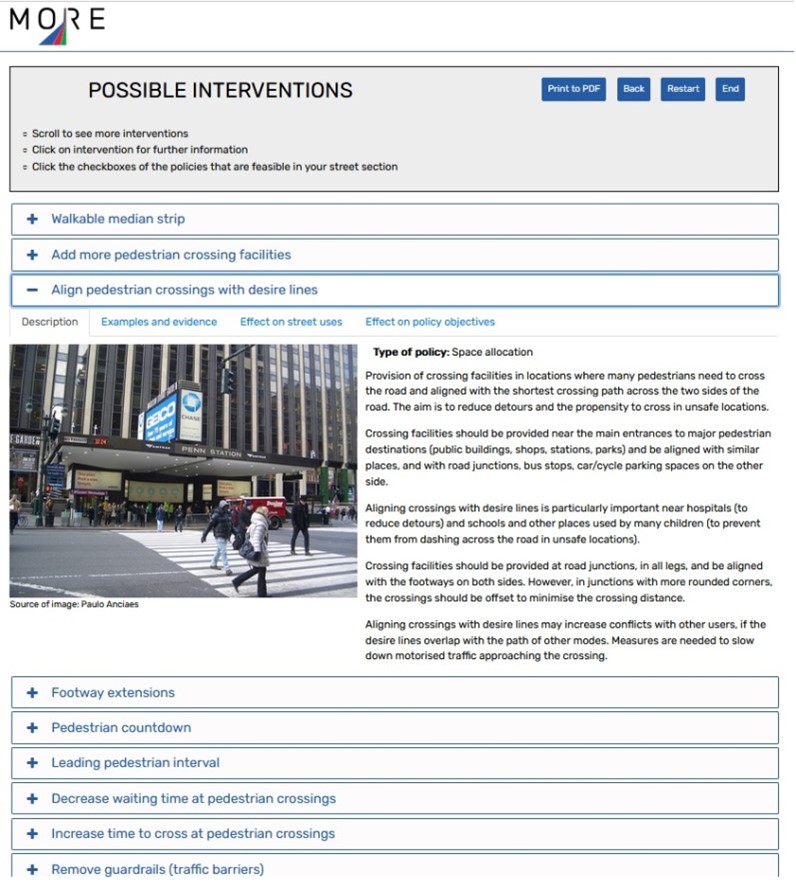

In an EU-funded project, we have developed tools to generate solutions to improve busy roads, including improving conditions for pedestrians. The tools are available from the International Federation of Pedestrians website.

One tool generates solutions to regulate, reallocate, or redesign road space. The user specifies the objectives (example: improve conditions for pedestrians without making bus users worse off). The tool returns solutions that have worked elsewhere. The user can then see detailed information about every solution. See an example below.

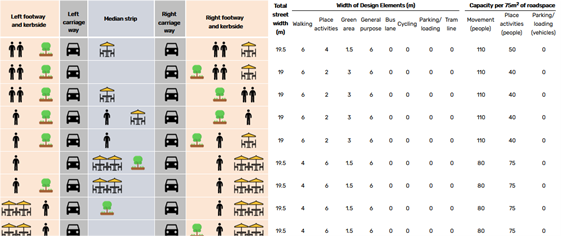

Another tool generates road designs, in cross section, that fulfil the user criteria (e.g., more space for pedestrians without removing space for buses) and that fit into the available street width. See an example of the tool’s output below.

4.3. Tools to assess solutions for barrier effects

Use them if: you are a practitioner or a member of the public and you have already thought of (or generated using the tools above) a set of possible solutions to improve a busy road. You now want to forecast the effects of those solutions and compare them.

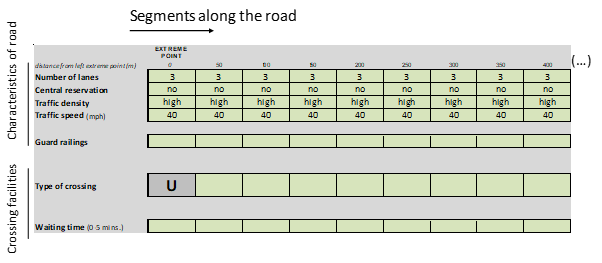

We developed a tool (available from the UCL website) to compare options to improve walking conditions in busy roads, for example, by reducing the number of lanes, reducing traffic volumes or speeds, or changing the number, location and type of crossing facilities. Below is an example of the tool interface. The tool quantifies the reduction in the barrier effect from 0 to 100. It then forecasts the number of additional walking trips and the benefits for pedestrians (in terms of money).

Monetisation is useful because decisions about transport investments often go through a cost-benefit analysis, i.e. quantifying the positive and negative impacts of the project as money. What is not quantified is appended to the analysis and described with words. In practice, these non-monetised impacts tend to be “hidden”, as the key message is the benefit-cost ratio. Our tool reduces this bias, by quantifying the benefits and costs for pedestrians.

Case studies

Applications of these tools are welcome. Please get in touch if you would like advice on how to use them or to report your results. Below are some examples of case studies using the tools:

Tools to identify barrier effects – Application in Finchley Road, London: Mindell, J. S., Anciaes, P. R., Dhanani, A., Stockton, J., Jones, P., Haklay, M., Groce, N., Scholes, S., Vaughan, L. (2017) Using triangulation to assess a suite of tools to measure community severance. Journal of Transport Geography, 60, 119-129

Tools to generate solutions for barrier effects – Application in five European cities (London, Lisbon, Malmö, Budapest, and Constanta): MORE Project report

Tools to assess solutions for barrier effects – Tool development case study in Hereford and Hull: Anciaes, P., Jones, P. (2020) A comprehensive approach for the appraisal of the barrier effect of roads on pedestrians. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 134, 227-250.

Other references

Anciaes, P. R., Stockton, J., Ortegon, A., Scholes, S. (2019) Perceptions of road traffic conditions along with their reported impacts on walking are associated with wellbeing. Travel Behaviour and Society, 15, 88-101.

Anciaes, P., Jones, P., Mindell, J., Scholes, S. (2022) The cost of the wider impacts of road traffic on local communities: 1.6% of Great Britain’s GDP. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 163, 266-287.

Anciaes, P., Nascimento, J. (2022) Road traffic reduces pedestrian accessibility – quantifying the size and distribution of barrier effects in an African city. Journal of Transport and Health 27:101522

Higgsmith, M., Stockton, J., Anciaes, P., Scholes, S., Mindell, J S. (2022) Community severance and health: measuring community severance and examining its impact on the health of adults in Great Britain. Journal of Transport and Health, 25:101368

In the spirit of academic peer review, THINK welcome referenced response blogs to encourage open discussion. If you would like to write a response blog please email think@aber.ac.uk with the subject line 'Blog Response'