THINK recently held a series of workshops where transport and health practitioners, researchers and policy-makers discussed the challenges and possibility for progression in improving public health through transport interventions and policy, while also working toward broader social and environmental goals.

One of the key themes that came from the discussions was collaboration. Suggestions included more collaborations across disciplines to get things done “on the ground”, to appreciate the input from different disciplines, to be less siloed in approach and to improve communication between transport and health practitioners, and academics and other stakeholders. Some of the barriers that arose were evidence-action gaps, a lack of contextual appropriateness to solutions and a difference in what evidence is counted as valid.

Transport planning as a discipline has historically relied on modelling the possible impact of different interventions to solve complex problems or to understand and predict people’s travel behaviours. Although it is necessary to understand general patterns, behaviours and needs, modelling for the average person has meant that many people are excluded from services and places we all have a right to. Public health research has traditionally used epidemiological quantitative methods to understand the cause of health conditions across populations or the effectiveness of interventions through ‘randomised controlled trials’. Yet, scenarios in the real-world continue to present challenges because of various complexities. For example, challenges to behaviour change are present because of environmental, cultural, and economic factors. Qualitative and participatory approaches are now informing planning, engineering, and public health disciplines, often complimenting them to examine behaviours and norms, and the impact of interventions, policies and other transformations in context. Yet, different ontological and methodological approaches of various disciplines, and even within disciplines, remain bound by sets of technical and cultural norms.

Exploring possibilities for collaboration with big and thick data

The rise of advanced computational analytics, such as machine learning, demands insightful data that can help to refine, calibrate, contextualize, or interpret routinely collected big data. At the same time, we need to recognize the capacity of big data analytics to scale, extend, validate, and generalize the insights derived from qualitative ‘thick data’ – ethnographic observations, interviews and narratives. For example, new research[i] is being used to combine emotion data – including body sensor and GPS data – with participant narratives and drawings that enrich what we can know about people’s experiences of their neighbourhoods. This enables people to share details of what they felt and why, embedding insights from sensor data on the ground to capture details of the problems encountered in people’s mobility. Such an approach may help us to improve the design and safety of spaces and the way we feel interacting in different spaces.

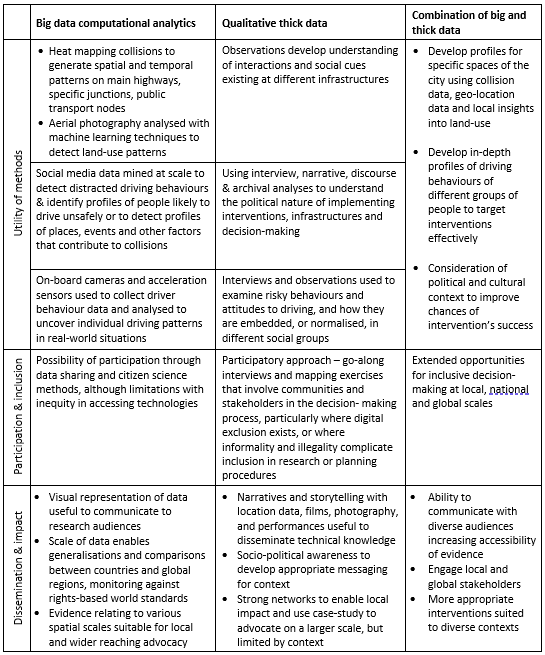

While working on the PEAK Urban project funded by the UKRI’s Global Challenges Research Fund, myself and colleagues found a common interest in considering how to overcome historical, ontological, disciplinary, and methodological boundaries. We recognised that being bound within a discipline can mean that we become familiar with certain ways of seeing and understanding problems and tackling them. We realised if we could learn to embrace our differences, we might stand a better chance of succeeding in collaborative endeavours. We identified a need to be more aware of how we each could contribute to a project or solution. So, we ran a discursive experiment to see how we would approach the issue of traffic collisions through a combination of our analytical lenses. The article is available open access in the Journal of Urban Affairs [ii] and summarises the strengths and weaknesses of both big and thick data analyses, the benefits of using both together, and the most recent collaborative techniques used in urban planning.

Reconciling methods in practice: road safety and traffic collisions in Mexico City

Our collaborative experiment considered a hypothetical case of road safety in Mexico to brainstorm how big and thick data could be used to develop knowledge to inform policy and interventions to reduce traffic collisions. The different methods we discussed and their use in a collaborative approach to road safety are detailed in the table below:

In our team, specialists in big data analytics outlined the advantages of the techniques they might use to identify patterns in collisions in certain spaces of the city at various times of the day and week. They described the kinds of real-time sensor data now used to examine driver behaviour and potentially to alter it real-time. But they thought there are gaps in our understanding of the attitudes of drivers and the political and societal impetus for action in traffic safety regulation and behaviour change. Our specialists in ethnographic and historical studies highlighted the contextual nature of the road safety problem.

We all accepted big data analyses can overlook the historical pathways giving rise to driver attitudes; pathways that are embedded in specific contexts that, over time, lead to the emergence of established social norms within different demographic cohorts or places. For example, conversations with drivers may reveal gendered ways in which driving fast is normalized, and how these norms, in turn, embody and express identities that are intensified under the influence of alcohol or certain social situations. Attitudes may change depending on a driver’s age, reflecting not only their level of experience but also the different ways in which identities are embodied through driving practices.

As in the THINK workshops, the political mechanisms that can determine the use of an intervention was raised as a barrier to making the city safer. During the 2018 Mexico City elections, a number of political candidates ran on a vehicle-centric manifesto to gain support by promising the removal of the city’s automated system that delivered fines to drivers breaking speed limits. The newly elected government of 2018 decided to retract the fining system, introduced in 2015, with the argument that it was exerting a detrimental economic impact on families, was costly to implement and was poorly designed. However, analysis revealed it was the likelihood of speeding and receiving a fine increased with income meaning at least one justification was not plausible. Developing a refined understanding of a city’s political and economic context—including the historical emergence of political networks and interest groups, and their relations with interventions – is a necessary part of embedding big data-driven methods within city governance.

Collaboration at different stages of research projects and interventions

One of the most significant contributions of taking a more integrated approach is the capacity to generate new insights and approaches that extend across all stages of the research process. Insights from big and thick data analyses can complement and feed into one another as part of a larger iterative and circular process of research design. For example, big data is useful for identifying where problems are most significant and for whom. Ethnographic research can assist with the identification of relevant stakeholders and to help determine how they should be engaged in the research process. Big data can be used to identify subgroups to be targeted for further ethnographic inquiry, through which specific behaviours and needs can be examined in detail. Furthermore, collaboration creates opportunities for disseminating evidence and communicating with different audiences to ensure relevant stakeholders are involved in decision-making processes, which may be useful in establishing long term democratic and inclusive decision-making.

Yet, collaboration is still lacking. Perhaps because it is challenging and poorly understood. For example, one barrier we faced as researchers was at publication because the inter-disciplinary journal we first submitted to involved four reviewers all of whom requested a research study that could demonstrate the hybrid approach in a real-world scenario. The second journal review considered our explorative discussions to be valid data. This highlighted how norms around knowledge validity are embedded in research publication and peer review. We need to be able to publish collaborative research findings without additional barriers. For example, inter-disciplinary journals can utilise editors who relate to different approaches and draw upon reviewers from different methodological disciplines to review each paper. This would balance out norms and perspectives on methods used in research. The problem of finding sufficient reviewers, however, reduces the possibility of neutral and collaborative review processes.

Another recommendation, that is not always possible, is time. It took patience for us to listen, learn and formulate our approach even hypothetically without real-world research challenges to overcome. It may be that many collaborative projects are not funded enough time to fully engage the iterative processes we have described, to learn co-productively, or to fully develop mutual understanding and cooperation. It takes more time to write collaborative proposals and research outputs. There is also a need for more research and resources on successful collaboration. It may not be the most likely impact output to appear on project proposals and rarely takes the centre stage in publications, but if we get collaboration working well, it is an impact in itself.

With thanks to the contributing researchers Andy Hong, James Duminy, Raphael Prieto Curiel, Bhawani Buswala, ChengHe Ghan and Divya Ravindranath.

PEAK Urban project has brought together early-career urban researchers from five countries (United Kingdom, India, China, Colombia and South Africa) to develop innovative and interdisciplinary ways of dealing with complex urban problems[iii] .

[i]Willis, K.S. and Nold, C., 2022. Sense and the city: An Emotion Data Framework for smart city governance. Journal of Urban Management.

[ii]Hong, A., Baker, L., Prieto Curiel, R., Duminy, J., Buswala, B., Guan, C. and Ravindranath, D., 2022. Reconciling big data and thick data to advance the new urban science and smart city governance. Journal of Urban Affairs, pp.1-25.

[iii]Keith, M., O’Clery, N., Parnell, S. and Revi, A., 2020. The future of the future city? The new urban sciences and a PEAK Urban interdisciplinary disposition. Cities, 105, p.102820.