Short briefing and FAQs

Author: Dr Sarah J Jones, THINK Co-Director, Consultant in Environmental Health Protection, Public Health Wales, Honorary Senior Lecturer, Cardiff University

1. What is Graduated Driver Licensing?

Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) enables new drivers to gain valuable driving experience under low risk conditions.

We know that for all new drivers, but particularly new young drivers, driving at night or with their friends as passengers or having consumed any alcohol is very high risk(1).

GDL reduces this risk by reducing exposure to these high risk situations(2). GDL gives the new young driver permission to drive unaccompanied, but not in high risk conditions, unless they are supervised by a fully qualified driver. It does this by adding an ‘intermediate’ phase between the learner and full licences, when these permissions are applied.

This intermediate phase lasts for a fixed period, up to 2 years in some places, and is linked to a fixed learner period of up to 1 year(3). The learner period also encourages certified driving over a set number of hours and in set conditions.

1.1 Is it needed in the UK?

Yes.

Around one in five newly qualified drivers in the UK crash within six months of obtaining their driving licence; most of these are aged under 25. Around four people are killed or seriously injured each day in the UK in crashes involving young drivers.

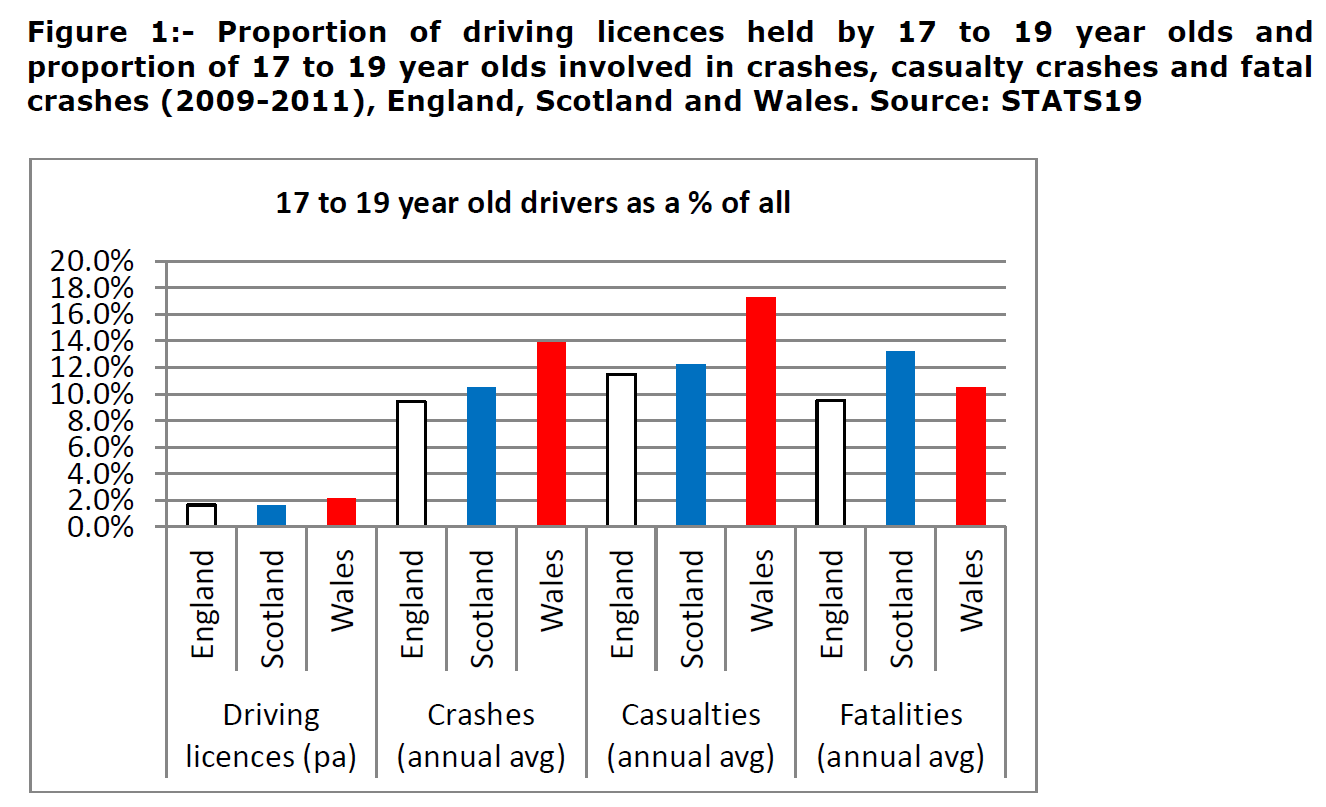

Drivers aged 17 to 19 years old hold around 2% of driving licences in the UK, but are involved in 10 to 14% of crashes, 12 to 17% of casualty crashes and 10 to 13% of fatal crashes (figure 1).

The crash risk of an 18 year old newly qualified driver is around 6 times higher than that of their parents and three times higher than that of a newly qualified driver aged 35(4).

In England, driver fatalities amongst males aged 17 to 20 years have been found to be 19.4 times higher than males aged 40 to 49. For females in the same age groups, the risk was 10 times greater(5).

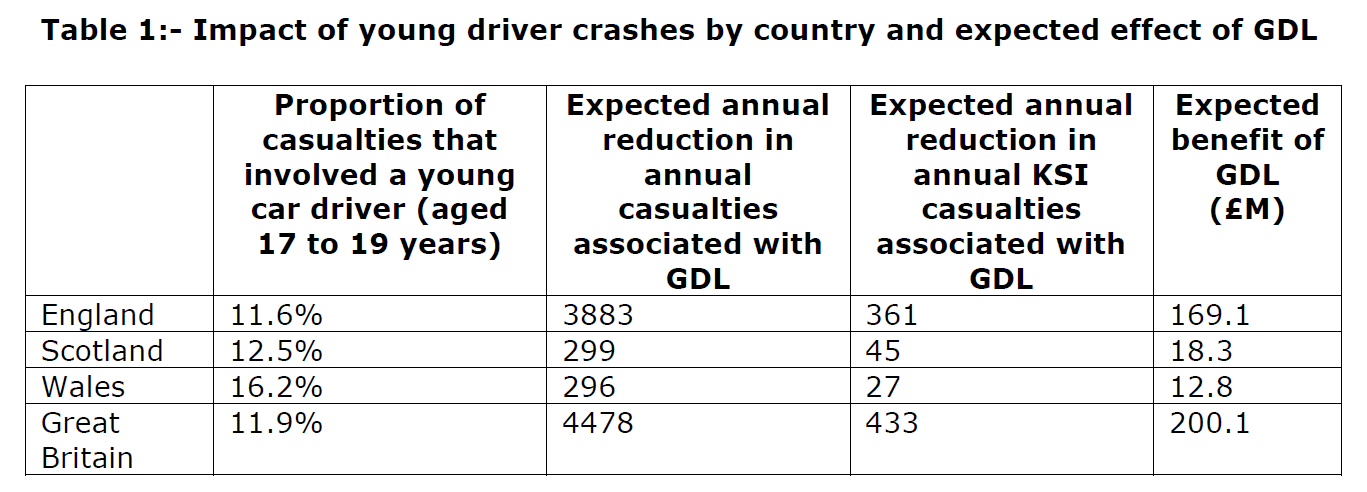

Recent data from the RAC Foundation6 show that in Wales, in particular, a greater proportion of crashes involve young drivers than anywhere else in Great Britain (table 1). Dyfed-Powys in Wales has a higher proportion of casualties that involve a young driver than any other region of Great Britain at 18.2%.

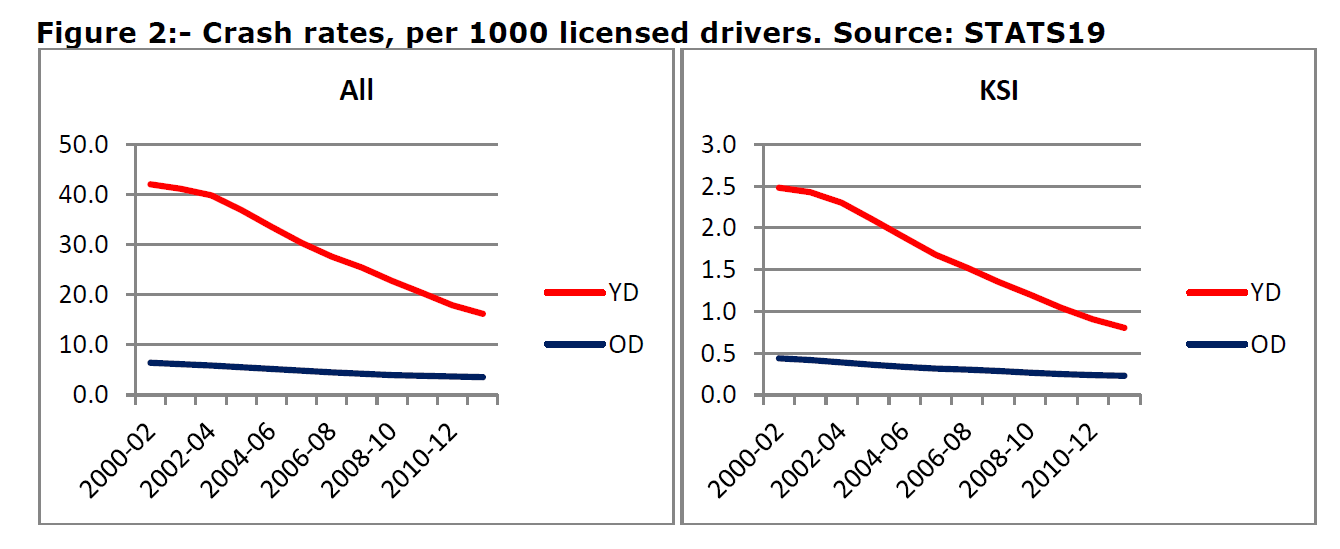

Across Great Britain, crash rates (per 1000 licensed drivers) for all crashes and KSI crashes amongst all drivers have been decreasing during recent years (figure 2).

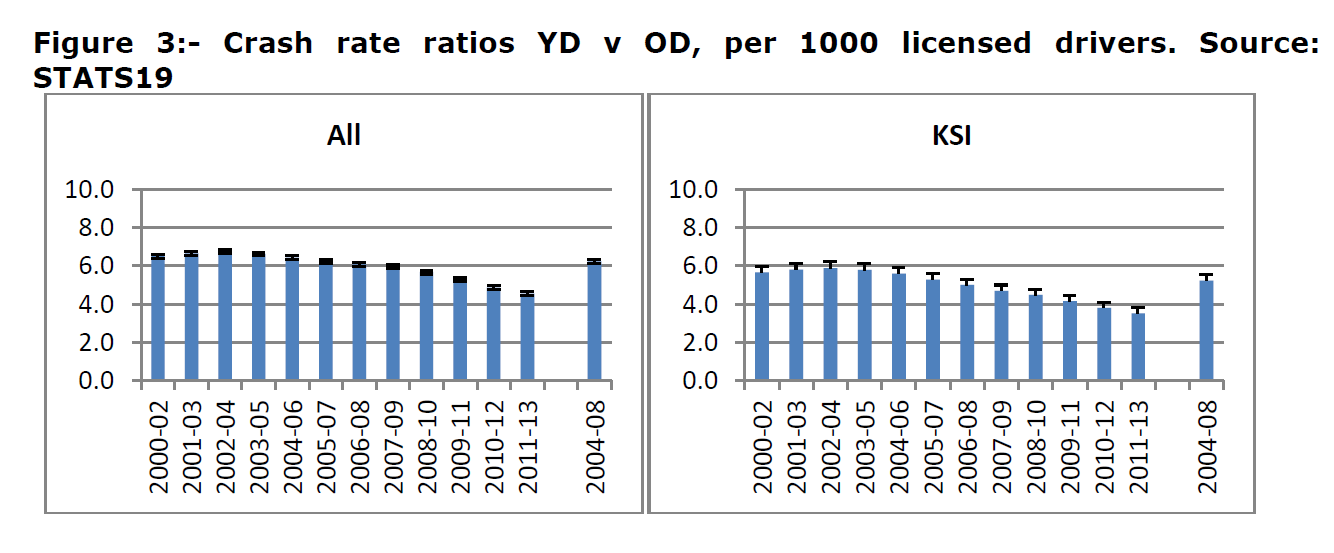

As a result, the ‘gap’ between young driver and older driver crash rates has narrowed from around 6 times to around 4 times for all crashes and KSI crashes (figure 3). However, there is still some way to go.

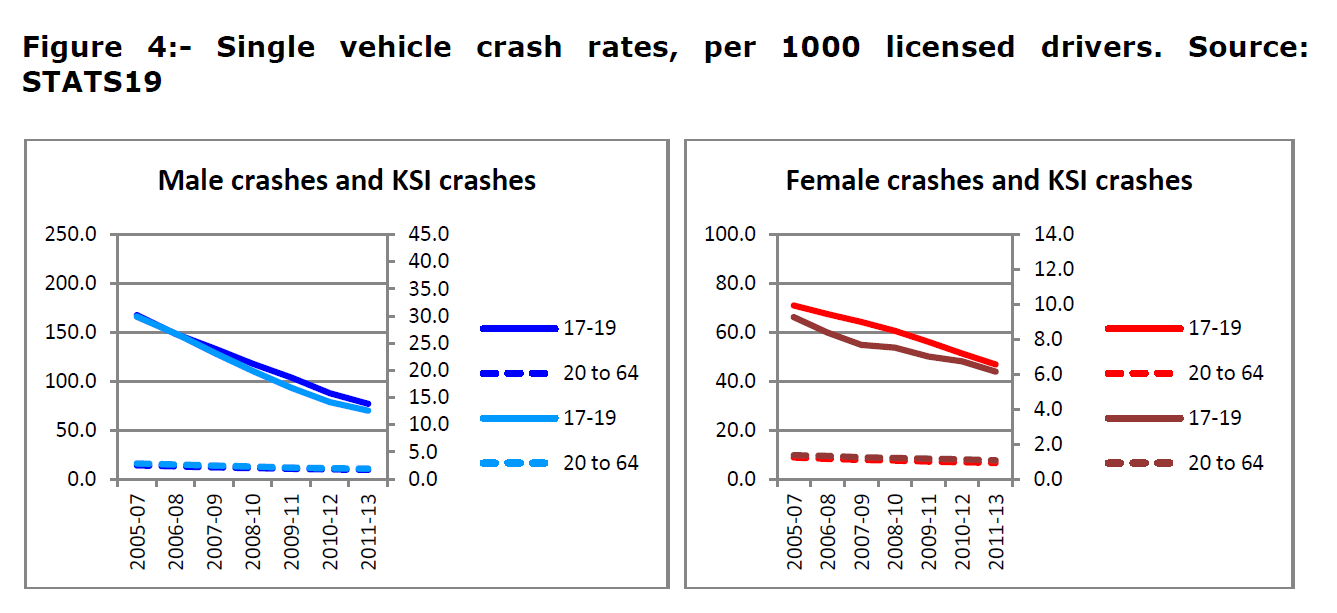

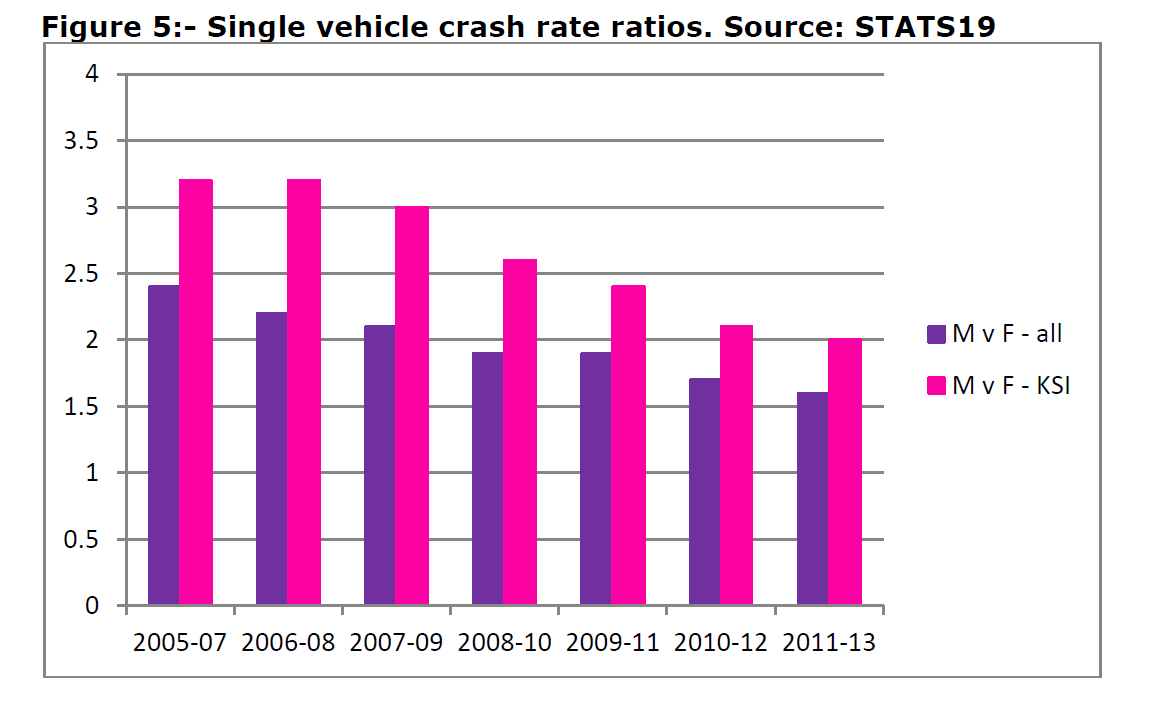

In addition, if we look only at single vehicle crashes by age and sex, although male crash rates always have been much higher than female rates, the decrease in male crash rates has been greater, in particular for young males.

As a result, the gap between young males and young females has narrowed significantly (figure 5).

1.2 Does it work?

GDL has been demonstrated to have only positive effects, both in terms fatalities, casualties and crashes, and in terms of outcomes such as teen and parent empowerment.

In 2013, a review by the Transport Research Laboratory, commissioned by the UK Department for Transport, found that there is compelling evidence that GDL has been effective at reducing collisions involving novice drivers wherever it has been implemented. It also noted that the quality and consistency of the evidence base is high and reductions in collisions are seen for novice drivers of all ages(7).

In 2011, a Cochrane review found that

“GDL is effective in reducing crash rates among young drivers, although the magnitude of the effect varies. The conclusions are supported by consistent findings, temporal relationship, and plausibility of the association. Stronger GDL programmes (i.e. more restrictions or higher quality based on IIHS classification) appear to result in greater fatality reduction” (Russell et al., 20118).

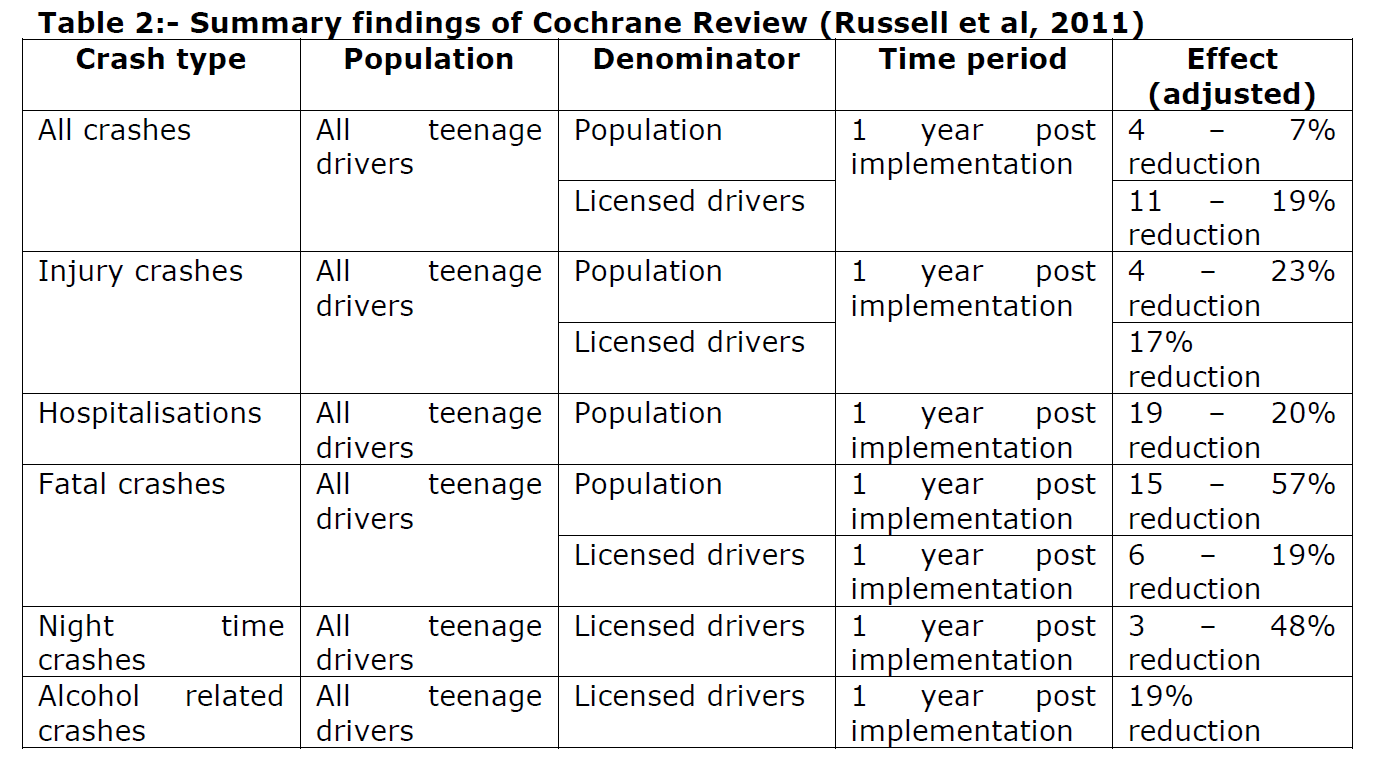

Calculating an overall effect of GDL is impossible because of the different social, cultural and environmental settings in which different programmes exist. However, summary findings from the Cochrane review have been produced (table 2). The biggest effect demonstrated by this review has been on fatal crashes, with a decrease of up to 57%.

1.3 Would it work in the UK?

There is no good reason why it would not work in the UK.

Obviously, it may be suggested that the UK is different to the countries in which GDL works, but, as shown by the Cochrane review, the countries in which it has been implemented, and in which it works, are all very different, yet there is still a significant impact on fatalities, casualties and crashes. It seems very unlikely that the UK would be the first place where that trend would be countered.

In addition, analysis of police crash data for the UK indicates that many fatalities, crashes and casualties occur every year in the high risk situations that are typically covered by GDL(9) and there is significant potential for crash, casualty and cost savings if GDL was implemented (table 1).

1.4 What other concerns are there?

A number of questions have been raised about whether the UK should implement GDL and why it may not be successful. However, there are many good evidence based counter arguments against these concerns.

The police are too busy to enforce GDL

- The police themselves, in the form of head of ACPO Roads Policing, Suzette Davenport, have expressed the need for GDL to be implemented. CC Davenport has stated that the police will find ways to address enforcement and the driver identification issues that go with this.

- However, in all GDL systems, parents are the primary enforcers(10). Research has found that parents are strongly supportive of GDL and do not feel that the restrictions are inconvenient(11).

- In addition, there is no evidence that enforcing GDL is any more difficult than any other road safety legislation and could be made easier with the requirement for new drivers to carry an identifier (e.g. a “P” plate)(7). Even where GDL is not strongly enforced, it still demonstrates effectiveness(7).

GDL would penalise the majority of law abiding teens

- Research in other places suggests that most teens involved in fatal crashes do not have prior violations or crashes on their records and so potential problem drivers cannot be identified easily(12). Many “model” teens are killed in car crashes(13). These findings are supported by the disproportionately high crash rate amongst young drivers.

GDL will hinder young people’s education or employment opportunities

- A study in New Zealand found little evidence that GDL caused any real practical difficulties such as travel to school or work for either males or females(14). Of the teenagers who were interviewed after being subject to GDL, just 8% said that the night time curfew affected their ability to find work, while 1% said that the passenger restriction affected their ability to find work.

- Williams et al (2001) found that young drivers use various means to adapt their travel behaviour to get around night time and passenger restrictions, without much problem(7).

- No evidence has been found that supports the notion that GDL significantly impacts upon the employability of young people(7).

- In addition, data from the DVLA in October 2012 showed that 571,647 17 to 19 year olds in England and Wales held driving licences. The estimated population of 17 to 19 year olds in England and Wales at that time was 2,164,900. Therefore only around 25% of 17 to 19 year olds hold driving licences. It is not unreasonable to suggest that the remaining 75% do not perceive their working or educational opportunities to be affected by not learning to drive. Therefore, it is unlikely that GDL will have a significant effect on these opportunities.

Restricting young drivers is unfair and restrictions will not be accepted or complied with

- The high casualty toll associated with young drivers on UK roads is also unfair and must be dealt with. In addition, research in other countries has found that

“both parents and teens are generally much more accepting of the kinds of restrictions that have long been recommended for high-quality GDL systems than is generally assumed(15)”

And that,

“by large majorities, the public wants enforced restrictions placed on young drivers before and initially after they receive their licences”(16).

A study of young people in New Zealand found that while only 26% supported all three GDL conditions (night time, passengers and alcohol), 78% would not breach the licensing conditions(17). In addition, 30% believed that the passenger restriction was convenient in that it removed their responsibility for driving others.

More young drivers will drive without a license

- A study by Frith and Perkins (1992) found that after the implementation of GDL the proportion of unlicensed drivers was almost unchanged918). However, applications for the driving test decreased and it is believed that this was due to young drivers being less inclined to drive.

- In the UK, the current cost of insurance for young people seems to be a greater risk for driving illegally than would be risked from implementing GDL.

Beliefs that crash risk will go up when the restrictions are lifted.

- What exactly happens to crash risk once the restrictions are lifted is not clear. What is clear though is that a considerable amount of driving experience will have been developed and the driver will be ‘older’, reducing the age effect that is a key young driver crash risk(19).

- Obtaining a definitive answer is complicated by the variety of GDL programmes that exist and the different exit ages from these programmes. Unravelling the effect of age from the programme itself is almost impossible.

- McCartt et al. (2010) found continued beneficial effects for 18 to 19 year olds, with significant decreases in fatal crashes and larger decreases when stronger GDL schemes were used(20). However, Neyens et al. (2008) showed no effect on crashes of 18 year olds who were no longer affected by GDL(21).

Beliefs that young drivers need a ‘trade off’ and reduced learner age.

- Increasing the learner age from 16 to 16.5 reduced the fatal crash rate in one study by 7%, the increase to 17 brought about a 13% decrease22. Global reviews of licensing age indicate that higher licensing age is associated with safety benefits(23).

- In Northern Ireland, the recent new driver licensing proposals included a reduction in the learner age. This was rejected.

Young people in rural areas will be unfairly penalised.

- The burden of young driver crashes is greater in rural areas than in more urban areas, because of the nature of the road network and the long distances to medical care. In relation to GDL, several surveys carried out in the USA have compared urban and rural areas and found that parents in rural areas support GDL and that it is equivalent to the support in urban areas(24).

Passenger restrictions will increase the number of young drivers on the road, increasing their exposure

- There is no evidence to support this notion7. If a strict GDL system is in operation, where the exposure is increased, it occurs in lower risk conditions(7).

Telematics can do everything that GDL does.

- There is no evidence to support this notion(7). It is possible that telematics may support GDL legislation, but it can not be a substitute for it. Telematics are vehicle specific making it difficult to apply GDL type rules via telematics when a single vehicle has multiple drivers of different ages or a new driver uses multiple vehicles(7).

Driver behaviour is the problem and better education and training is the answer.

- There is no evidence that education and training can substitute for driver experience on-road or reduce novice driver collisions(7). In GDL schemes where time discounting was allowed for participation in driver education or training, evidence suggests that crash risk was increased(7)

2 Conclusions

There is consistent, robust evidence of the effectiveness of GDL in terms of crashes, casualties, fatalities and hospitalisations. In addition, data for the UK show that young driver crashes and casualties occur in the UK in the circumstances covered by GDL.

“The evidence that Graduated Licensing improves safety is compelling. Driver licensing in GB should be based on a strong Graduated System”

Kinnear et al, 2013

A strong Graduated Driver Licensing programme now needs to be developed and implemented in the UK.

REFERENCES

1 Braitman, K.A., Kirley, B.B., McCartt, A.T. & Chaudhary, N.K. (2008). Crashes of novice teenage driver: Characteristics and contributing factors. Journal of Safety Research, 39, 47-54.

Rice, T.M., Peek-Asa, C., and Kraus, J.F. (2003). Nighttime driving, passenger transport and injury crash rates of young drivers. Injury Prevention, 9, 245-250.

Williams, A.F., Ferguson, S.A., & Wells, J.K. (2005) Sixteen year old drivers in fatal crashes, United States, 2003. Traffic injury prevention, 6, 202-206.

2 Ferguson, S.A. (2003). Other high risk factors for young drivers – how graduated licensing does, doesn’t, or could address them. Journal of Safety Research, 34, 71-77.

Braitman, K.A., Kirley, B.B., McCartt, A.T. & Chaudhary, N.K. (2008). Crashes of novice teenage driver: Characteristics and contributing factors. Journal of Safety Research, 39, 47-54.

3 Begg, D.J., Stephenson, S., Alsop, J. & Langley, J. (2001). Impact of graduated driver licensing restrictions on crashes involving young drivers in New Zealand. Injury Prevention, 7, 292-296.

Ferguson, S.A. & Williams, A.F. (1996). Parents’ views of driver licensing practices in the United States. Journal of Safety Research, 27, 2, 73-81.

4 Twisk, D.A.M. and Stacey, C. (2007). Trends in young driver risk and countermeasures in European Countries. Journal of Safety Research, 38, 245-57.

5 Mindell, J.S., Leslie, D., Wardlaw, M. (2012). Exposure based, like for like assessment of road safety by travel mode using routine health data. PLoS ONE 7(12): e50606. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050606

6 Kinnear, N., Lloyd, L., Scoons, J. and Helman, S. (2014). Graduated Driver Licensing. A regional analysis of potential casualty savings in Great Britain. RAC Foundation. London.

7 Kinnear, N., Lloyd, L., Helman, S., Husband, P., Scoons, J., Jones, S., Stradling, S., McKenna, F. And Broughton, J. (2013). Novice drivers: Evidence review and evaluation. Published Project Report PPR673. Transport Research Laboratory. Crowthorne.

8 Russell, K.F., Vandermeer, B., Hartling, L. (2011). Graduated Driver Licensing for reducing motor vehicle crashes among young drivers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 10. Art. No.:CD003300. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003300.pub3.

9 Jones, S.J., Begg, D., and Palmer, S.R. (2012). Reducing young driver crash casualties in GB – use of routine police crash data to estimate the potential benefits of graduated driver licensing. Injury control and safety promotion, DOI:10.1080/17457300.2012.726631.

10 Williams, A.F. (1999). Graduated licensing comes to the United States. Injury Prevention, 5, 133-135.

Foss, R. And Goodwin, A. (2003). Enhancing the effectiveness of graduated driver licensing legislation. Journal of Safety Research, 34, 79-84.

11 Brookland, R. & Begg, D.J. (2011). Adolescent, and their parents, attitudes towards graduated driver licensing and subsequent risky driving and crashes in young adulthood. Journal of Safety Research, 42, 109-115.

Ferguson, S.A. & Williams, A.F. (1996). Parents’ views of driver licensing practices in the United States. Journal of Safety Research, 27, 2, 73-81.

12 Williams, A.F. (1999). Graduated licensing comes to the United States. Injury Prevention, 5, 133-135.

13 Williams, A.F. (2006). Young driver risk factors: successful and unsuccessful approaches for dealing with them and an agenda for the future. Injury Prevention, 12 (Suppl I):i4-i8.

14 Brookland, R. And Begg, D. (2011). Adolescent, and their parents, attitudes towards graduated driver licensing and subsequent risky driving and crashes in young adulthood. Journal of Safety Research, 42, 109-115.

15 Foss, R. And Goodwin, A. (2003). Enhancing the effectiveness of graduated driver licensing legislation. Journal of Safety Research, 34, 79-84.

16 Gillian, J.S. (2006). Legislative advocacy is key to addressing teen driving deaths. Injury Prevention, 12, (Suppl I): i44-i48.

17 Begg, D.J. and Stephenson, S. (2003). Graduated driver licensing: the New Zealand experience. Journal of Safety Research, 34, 99-105.

18 Frith, W.A. & Perkins, W.A. (1992). The New Zealand graduated driver licensing system. Conference proceedings from National Road Safety Seminar, Wellington, New Zealand, vol 2 (pp. 256-278). Road Traffic Safety Research Council.

19 Williams, A.F. (2006). Young driver risk factors: successful and unsuccessful approaches for dealing with them and an agenda for the future. Injury Prevention, 12 (Suppl I):i4-i8.

20 McCartt, A. T., Teoh, E.R., Fields, M., Braitman, K.A., & Hellinga, L.A. (2010). Graduated Licensing laws and fatal crashes of teenage drivers: A national study. Traffic Injury Prevention, 11, 3, 240-248.

21 Neyens, D.M., Donmez, B., & Boyle, L.N. (2008). The Iowa graduated driver licensing program: effectiveness in reducing crashes of teenage drivers. Journal of Safety Research, 39, 383-390.

22 McCartt, A. T., Teoh, E.R., Fields, M., Braitman, K.A., & Hellinga, L.A. (2010). Graduated Licensing laws and fatal crashes of teenage drivers: A national study. Traffic Injury Prevention, 11, 3, 240-248.

23 Begg, D.J. and Langley, J. (2009). A critical examination of the arguments against raising the car driver licensing age in New Zealand. Traffic Injury Prevention, 10, 1-8.

Williams, A.F. (2009). Licensing age and teenage driver crashes; a review of the evidence. Traffic Injury Prevention, 10, 9-15.

24 Gill, S., Shults, R.A., Cope, J.R., Cunningham, T., Freelon, B. (2013). Teen driving in rural North Dakota: A qualitative look at parental perceptions. Accident Analysis and Prevention, on-line first.